The Value Of A Life

Krystal L.

Smith

I

found myself sitting terrified in a perinatologist's office, waiting

to determine if the blood screen for trisomy 18 was truly positive.

After a level II ultrasound, the doctor said he did not see any

markers of T18. I was offered a CVS, and opted to have it. As we

chatted about the testing procedure, he pointed to the door and said,

“If you look on the bulletin board in the hallway there are women

on it who had a trisomy diagnosis, terminated, then had a healthy

pregnancy and baby the very next try. If you wanted to be more

discreet we can send you to another city. If you choose to carry, we

will support you, but your baby will suffer when it is born. He will

suffocate. They can give him morphine, but it will be very painful.

In

medicine, I have heard it a thousand times. “I took an oath to

first do no harm.” What I have found in my time spent in the

hospital, is that what is ethical is extremely subjective. I have

many thoughts on what the value of life is, how human beings should

be treated, and ultimately the role of healthcare professionals in

deciding the treatment of any person in need. My goal is to express

the view point of a mother with a medically complex child on matters

such as ethics, treatments, and research.

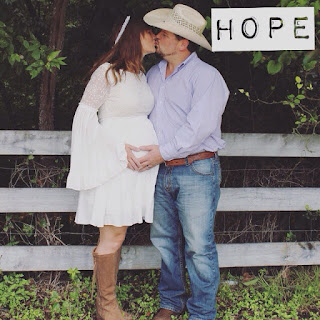

When

I look back on the conversations I had with a variety of doctors

during my pregnancy, I cannot remember a single time hope was offered

to me. I was never told there are living trisomy 18 children. The

terms used most frequently were “not compatible with life,” and

“not a viable pregnancy.” I chose to carry my son to term, though

I was told he would likely pass in utero. There were many days in

that first trimester I wondered how I could carry on. My heart so

full of love for a baby who wasn't going to be here very long. How

will I do this? I promised him from the time I knew he existed, I

will give you your best chance. I decided that wasn't going to change

because of a diagnoses. From then on, I did everything in my power to

help him. I ate well, I exercised, I took supplements and vitamins, I

drank water until I would nearly float away. Anything I could do to

help him, I did. As time went on, I began to have a little hope;

cautious hope.

Calloway

Augustus, “Gus” as we lovingly call him, had to be induced at

just over 41 weeks gestation. The baby who wasn't supposed to make it

to a live birth was going to be born. I had met with a team of

doctors and nurses who said they would make sure my birth plan was

understood and followed. They promised Gus would receive the

interventions I asked for. Everything was planned. NICU was supposed

to be there for his birth, everyone knew I wanted full interventions

unless otherwise stated. I was assured that we would be taken care

of.

December

6, 2016 a beautiful baby boy entered this world. He was born without

a doctor present, without the NICU team we were promised, and

ultimately lived in spite of the lack of care. We had been told he

could be monitored in the delivery room to remain close to us during

our prenatal care conference. All of a sudden this was not true, and

we were told we could just hold him and spend time with him alone. If

he turned blue, they said they could be back in 10 minutes. My family

insisted they take him to the NICU since they refused to monitor him

in the delivery room. Away little Gus went, crying and breathing on

his own.

The

care we received in the NICU was poor. While they did give him oxygen

as needed and a feeding tube, they refused to do anything else. My

mother and sister had done extensive research on living trisomy 18

children and knew the common problems associated with the chromosome

abnormality. They knew what tests we needed and why we needed them.

We were refused all testing we requested with the exception of an

echocardiogram. At one point I was told by a doctor that nobody sees

the economic value in trisomy children and that it is considered

silly to intervene. He told me he had a child with a chromosome

abnormality, and that there was no way he was going to give up his

lifestyle to deal with that. He and his wife terminated the

pregnancy. He told me people will be cruel, say horrible things to

me, and that my marriage will crumble. He said my life would be over,

and that I am a much better person that he is. While he stated he was

a Christian, and his wife is a saint... I am certain he is very

confused about what that means. We were sent home after two weeks and

remained there about ten days before sweet Gus started having O2

desaturations to the point we had to take a helicopter ride to a

children's hospital. We never retuned to the hospital I gave birth

in.

Upon

arrival, we were told Gus likely had a respiratory virus. With Gus's

diagnosis, he knew that we wanted as much time with our son as

possible and they hoped to give me that time. I looked at him and

told him I know his diagnosis, and that our goal is to get well and

go home. He stated it was clear that I understood what Gus has, and

he will put a note for other doctors not to give me “the talk”

again. He was treated for respiratory distress and recovered quickly.

While we were there originally for respiratory distress and apnea,

other problems were discovered and discussions about treatments and

the degree of interventions began to be discussed. I was told

repeatedly there was no reason to do a sleep study, that apnea was

apnea, and what difference was it really going to make? I was told

that a tracheostomy would not be helpful to my son because he had

central apnea, and he would be vent dependent with no quality of

life.

This

doctor with another backing him up, went as far to tell me he hoped I

would be reasonable and not do “too much.” He claimed we do too

much for these kids in this country. He also stated that if he was in

a car accident, he would come back to haunt his wife if she ever got

him a tracheostomy and a vent. He said he told her to let him die,

because he would be miserable. One of the reasons he said it would be

unfair, is that my son would not be able to swim under water and I

would never hear his voice again. His idea of quality of life is

apparently going under water in a swimming pool. According to him,

once you are trached you are always trached and nobody ever gets off

of a vent. He pressed me to answer him about whether or not I would

consider a trach for Gus, and I mumbled well no, I would never want

to hurt him. During this time, I knew little about trachs or vents. I

only had the information he wanted me to have. Unfortunately, I was

only being told one extreme in a large spectrum and being fed a lie

that suited this particular doctor's “ethics”. Later, because of

a very special pulmonologist who has living t18 patients, we were

offered the sleep study that I had desperately wanted. It was

determined that Gus did not have central apnea, he in fact had the

most severe case of obstructive apnea this hospital has ever seen.

After doing my own research and speaking with the tracheostomy nurse,

I learned children get decannulated all the time and vent weening is

standard procedure. Yes it is possible you always have a trach or

always need a vent, but I was told nobody ever gets rid of either.

The trach nurse and I talked about what life looks like with a trach,

and she explained Gus could have a great quality of life! Even if he

needed a vent, it would not keep him from a great life. She explained

the trisomy children are her favorite, and they definatly have a

place in this world. Her view was quite different from the other two

doctors who continuously told me a trach was a bad idea. As I look

back, I remember thinking, isn't not being able to breathe a worse

idea?

One

of the repeated arguments I hear is how uneconomical it is to

intervene for trisomy children when they have such a limited life

expectancy. The question is often why would we do anything, go to all

the trouble and spend all this money on a child who will be a

vegetable. There are several points to be make in opposition to this

argument. First, trying to base the value of a human life in monetary

terms is absurd. Ask anyone who has lost someone they love what they

would give for one more day, 5 more minutes, or one last hug. The

answer is usually a simple one. “Anything.” Have you ever heard

someone say, “Well, I would give 200 dollars, but any more than

that would be uneconomical.”

It

seems discriminatory that there are some chronic illnesses that are

deemed worth treating, even if the outcome is dark, but others are

deemed not worth the effort. I have always compared it to things such

as cancer or cystic fibrosis. We don't just give up on giving those

kids their best chance, so why is it that something like an extra

chromosome devalues your right to treatments and your best chance at

life?

There

is a huge misconception when it comes to trisomy 18 in particular.

There are living children who are thriving. They are far from the

vegetables that their parents were told they would be. These children

are full of personality. They smile, laugh, cry, and communicate. I

am puzzled as to why these stories and the wide range of outcomes is

not explained to the parents by physicians. Why are doctors not

reaching out to groups such as Rare Trisomy Parents on facebook to

see the wide range of trisomy outcomes and all the things these

children can do. At what point will physicians start looking

at the dates of the research they are reading and realize this is a

different day and age. The majority of studies conducted were in the

1960's. Medicine has come a long way since then, the problem now is

an ethical one.

Another

argument I often hear from the medical field, is that these children

are burdens to caregivers and ultimately destroy family

relationships. I would argue that trisomy 18 children are some of the

most loved in the world. I do not know one parent of a living or

deceased trisomy 18 child who regretted their decision to carry their

baby and do all they could to help them live. My child is not a

burden to me or to my family. We love and cherish every moment, every

single day. No one feels burdened. The biggest burden we carry is the

fight for equal rights to medical care. The stress from this aspect

is the most unbearable at times. Our children teach us lessons others

may never know and fill our hearts with the most joy imaginable. To

call them a burden is insulting.

Every

child is an individual. The range of outcomes goes from mild to

severe with all trisomies. Not everyone fits into one box. How can we

limit interventions when we cannot say with certainty how a child

will be effected? Is it not worth trying simply because there is an

unknown factor? Would we do that to a child who does not have an

extra chromosome? What is it that determines who lives and who dies,

who gets treatment and who doesn't, who is worth the effort and who

is not? A diagnosis is not a prognosis. To deny a child care, who

cannot speak for themselves is unethical. Doctors have a right to

deny care if they feel it is unethical to intervene, but they should

refer parents to someone who will treat the child if they see it as

the best option. Often people think they know what they would

do if it was their child. But truth be told, you don't know until it

is your child. What is the value of a life? It is

invaluable. You can't put a price tag on love.